Notes from Finland

International Piano, May/June 2015

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, a remarkable artist whose piano works deserve greater praise, writes pianist Joseph Tong

Last Summer as part of my research for my Sibelius disc for the Quartz label, I came across a recording of the Japanese pianist Izumi Tateno performing Sibelius on the composer’s Steinway at Ainola. The beauty and originality of the music aroused my curiosity and I quickly set about acquiring scores – a mission that resulted in a rewarding voyage of musical discovery.

Arriving at Ainola early one morning during the July heatwave, I was thrilled

to be given special permission to play the composer’s beautifully maintained Steinway. To feel the keys under my fingers was both humbling and exhilarating.

Later the same day, I took a train to Hämeenlinna, the birthplace of Sibelius (the house where the composer was born on 8 December 1865 is now a museum).

Among other items on display, I was fascinated to see the original upright piano

(complete with candelabra which Sibelius used for his practice from the mid-1870s

onwards, as well as an autograph score of the opening bars of Finlandia.

In this article, I will restrict myself to writing about the repertoire on the Quartz disc, which I will also be performing in an all-Sibelius solo piano recital at St

John’s Smith Square this spring. With the possible exception of the early Sonata

in F major of 1893, Kyllikki Op 41 (1904) is probably Sibelius’s most significant

large-scale piano work of more than one movement. There is no complete certainty

of its connection with the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, but it can nonetheless

be seen as a triptych portraying Kyllikki and her three successive states of mind.

Whereas Kyllikki marks the end of Sibelius’s national romantic period, The Trees (1914) is a fine example of his later, highly cultivated piano style. Impressionist and expressionist influences are detectable in these exquisite nature-inspired miniatures. The fragility of the gradually unfolding right-hand melody suggests the

long-awaited flowering of the mountain ash (When the Mountain Ash Blooms), while the absolute steadfastness of the pine tree (The Solitary Fir Tree) was at the time interpreted as a symbol of Finland standing firm against Russian influence. Within the third piece, The Aspen, there is a growing harmonic ambiguity and an increasingly inward-looking expression. Of particular note are the tremolo passages, perhaps depicting branches quivering in the icy breeze, and the mournful ‘cello’ theme with its sparse accompanying chords. The Birch is the most energetic piece of the set, the favourite tree of the Finns, which ‘stands so white’. The rich tenor register is the natural

home for The Spruce’s slow waltz theme,

answered by an equally poignant melody

in the soprano before the sudden, dramatic

arpeggiations of the Risoluto section recall

the inner determination and strength of

The Solitary Fir Tree.

COMPOSED IN THE YEARS 1916-17,

The Flowers Op 85 is an

indispensable companion set to

The Trees. Bellis (daisy or daisies) is musicbox-like in style, using the white keys of

the piano and tiny, pinpointed staccatos to

depict perhaps a cluster of daisies sparkling

in the spring breeze. Oeillet (‘Carnation’)

is more overtly romantic, a beautiful waltz

with a brief minor variation and whimsical,

decorative passages in the upper melody. Iris

has a more improvisatory feel and serious

character, with its nuanced, leggiero runs

Notes from Finland

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of

Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, a remarkable artist whose

piano works deserve greater praise, writes pianist Joseph Tong

© MIKA TAKAMI, WITH KIND PERMISSION OF

THE AINOLA FOUNDATION, JARVENPAA, FINLAND

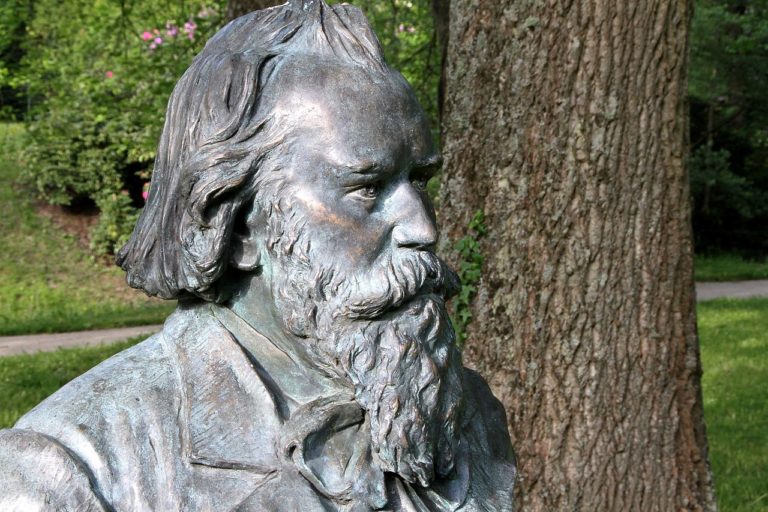

Joseph Tong pictured

outside the home of Jean Sibelius

May/June 2015 International Piano 61

REPERTOIRE

and delicate trills, while No 4, Snapdragon,

has a rhythmically taut opening theme

and later reveals some Schumannesque

accompaniments and harmonic sequences.

Campanula begins with a succession of

reverberating bells in the form of split

octaves in the treble, later conveying a

more nostalgic mood through ruminative

arpeggiations and expressive appoggiaturas

before ending poignantly with distant,

repeated bells in the top register.

The first of Sibelius’s three Sonatinas

Op 67 heralds a noticeable change in

style. It opens with a joyful, sparsely

harmonised theme and expresses a wealth

of musical ideas, through pithy twopart writing and other extraordinarily

economical means. The work’s slow

movement is particularly beautiful and

provides its emotional core. The quirky

and pianistically challenging finale

is characterised by some unexpected

harmonic diversions, an agitated minor

key melody in the left hand set against a

recurring, somewhat unsettling broken

octave accompaniment in the high register.

The two Rondinos Op 68 (1912) are

also distinctive and notable in a stylistic

sense, similarly dating from Sibelius’s

period of ‘modern classicism’. The G sharp

minor Andantino is full of questioning

pauses, sighing motifs and extremely

delicate, pianissimo winding melodies.

Its companion piece is remarkable for its

sharp dissonances and waspish humour,

together with nimble right hand tremolo

effects (in tenths) resembling stringcrossings on the violin.

The Five Romantic Pieces Op 101 (1923-

1924) reveal a richer handling of the

piano and Sibelius’s growing preference

for orchestral sonorities, with occasional

similarities to the Sixth Symphony. The

opening Romance was written in a suitably

tender, heartfelt vein as a reconciliation

gift to his wife Aino. Chant du soir, on the

other hand, is more succinct and less lavish

in texture and harmony, though no less

touching in its overall effect. A serenely

unfolding Andante introduction to Scène

lyrique gives not a hint of what is to come;

a rapid, polka-like Vivace which rattles

along in a violinistic fashion. Burlesque is

full of swagger and comical touches such

as teasing harmonic twists and hilarious

‘crushed-note’ chords, closing with a lighthearted, scampering coda. Calm is restored

with the dignified and beautifully crafted

Scène romantique, in which Sibelius shows

his mastery of the miniature forms and

paces the moment where the imagined

reconciliation occurs to perfection.

Sibelius’s Esquisses (1929) are the last

pieces that he composed for solo piano.

Remarkably, these were not published until

1973 and are still not very widely known.

Written towards the end of the composer’s

last active creative period, they explore

modal tonality and other compositional

devices such as tonal meditation (for

example in Forest Lake) while reflecting

an increasingly personal response to

nature, coupled with a bold, more radical

approach to harmony. For me, the most

striking of the set are Forest Lake and

Song in the Forest. Beyond the immediate

pictorial associations there lurks a darker,

more disturbing undercurrent and blurred

edges are perhaps what the composer had

in mind when considering the important

role of the sustaining pedal in both pieces.

Finally, Spring Vision has a deceptively

straightforward opening but its restless

Animoso theme also suggests that a feeling

of springlike optimism may be no more

than fleeting.

THE MOST SUCCESSFUL AND

frequently performed of Sibelius’s

orchestral transcriptions is his

celebrated version of Finlandia Op 26

(1899-1900). In addition to virtuoso

semiquaver flourishes, double octave

cascades and swirling arpeggiations,

Sibelius also uses the different registers

of the piano to great effect in recreating

something of the warmth of the string

sound in the hushed, cantabile ‘hymntheme’ and its subsequent development.

There is also something irresistibly spinetingling about launching into Finlandia’s

powerful opening chords, complete with

menacing tremolos, on a full-size concert

grand, and the translation of the tone poem

to the sound world of the piano seems to

work very successfully.

Whatever the underlying reasons for

the relative neglect of Sibelius’s piano

music, I hope that this year’s anniversary

celebrations will prompt a resurgence

of interest in this rich seam of repertoire

which spans virtually the entire period of

Sibelius’s creative life.